Have you ever brought a bottle of wine, flowers, or chocolate babka to a dinner party as a host/hostess gift? Or brought home a souvenir for your parents, partner, or kids after you’ve been travelling – like chocolate from Switzerland or, uh… Brazil nuts from Brazil? Countries do the same thing, kind of.

Diplomatic gifts are often exchanged when dignitaries travel abroad or receive visitors. They can be lavish, like a $780,000 emerald and diamond jewellery set, given by King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia. They can be modest, like a $50 bottle of wine, given by President Stjepan Mesić of Croatia. Or they can be essentially worthless, but symbolic, like a live shamrock, given by Prime Minister Bertie Ahern of Ireland. (Though in the shamrock’s case, the State Department did value it at $5.)

Do countries tend to give distinctive gifts? A shamrock is meaningful coming from an Irish Prime Minister, but it would feel less appropriate if it came from, say, the Prime Minister of Japan.

We’re going to perform a text analysis of diplomatic gifts to U.S. federal employees, which includes folks like the President, Vice President, and Secretary of State. By law, these gifts must be described, valued, and recorded. All this information is published publicly, which is what we’ll use as data to answer our question.

Setup

First, we’ll load the tidyverse and some other useful packages:

tidytextfor text analysisfishualizefor beautiful ggplot2 colour palettesextrafontfor additional fontsggtextfor rich-text customization of text (e.g., changing colours of individual words in a plot title)

Then we’ll import our data, originally from the U.S. Office of the Federal Register, which provides access to federal government documents, including the reports of diplomatic gifts that we’re looking for. The original documents needed extensive cleaning to get into a tidy format. I won’t go into detail on that process here, but if you’re interested, look at the README on GitHub.

library(tidyverse)

library(tidytext)

library(fishualize)

library(extrafont)

library(ggtext)

theme_set(theme_light())

gifts <- read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/tacookson/data/master/us-government-gifts/gifts.csv")

Data inspection

Let’s unwrap gifts!

# glimpse bottom of data because top doesn't have good examples

gifts %>%

arrange(-id) %>%

glimpse()## Rows: 8,392

## Columns: 10

## $ id <dbl> 8390, 8389, 8388, 8387, 8386, 8385, 8384, 8383, 83...

## $ recipient <chr> "Ms. Laura Vincent, Scheduler, Office of Senator M...

## $ agency_name <chr> "U.S. Senate", "U.S. Senate", "U.S. Senate", "U.S....

## $ year_received <dbl> 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 20...

## $ date_received <date> 2018-06-26, 2018-01-19, 2018-12-20, 2018-10-02, 2...

## $ donor <chr> "Their Majesties King Abdullah II bin Al- Hussein ...

## $ donor_country <chr> "Jordan", "Pakistan", "United States", "South Kore...

## $ gift_description <chr> "Money clip featuring the Raghadan Palace. Rec'd--...

## $ value_usd <dbl> 50.00, 115.00, 129.00, 110.28, 224.00, 146.00, 270...

## $ justification <chr> "Non-acceptance would cause embarrassment to donor...There are four types of data:

- Who received the gift, including name/title and what agency they are associated with

- Who gave the gift, including name/title and the country they represent

- Details on the gift itself, mostly in the written

gift_description, but also in thevalue_usdfield, which gives the estimated value - Details about the actual act of exchanging gifts, like when it was received and the reason the gift was accepted

We’ll focus on the gift_description field, which has wonderful free-form text descriptions. (I spent hours reading some of these descriptions.) Here is a short example of a gift given in 2003 to First Lady Laura Bush by French President Jacques Chirac.

gifts %>%

filter(id == 1605) %>%

pull(gift_description)## [1] "Accessory: 52'' x 52'' blue silk and cashmere Hermes scarf with scroll pattern. Recd-- September 29, 2003. Est. Value--$760. Archives Foreign."(We’ll soon see from our analysis that Hermès items are a quintessentially French gift.)

Text analysis with TF-IDF

These descriptions are great, but how do we use them to answer our question? In Text Mining with R, David Robinson and Julia Silge note that “a central question in text mining and natural language processing is how to quantify what a document is about” (emphasis mine). One way we can do that is by looking at the individual words that make up a “document” (in our context, document = gift description). If a word (like Hermès) shows up a lot in descriptions from a certain country (like France), then we can make the argument that that word is representative of that country’s gifts. It gets more complicated than that, but for now let’s see if we can split up these descriptions into their component words – a process known as tokenizing. We’ll use unnest_tokens() from the tidytext package.

Tokenizing gift descriptions

gift_words_raw <- gifts %>%

# Select unique gift descriptions to pare down gifts that often take up multiple lines

distinct(gift_description, .keep_all = TRUE) %>%

transmute(id,

donor_country,

gift_description = str_to_lower(gift_description)) %>%

# Filter out travel, which isn't interesting

filter(!str_detect(gift_description, "travel")) %>%

# Break gift_description into individual words

unnest_tokens(output = word, input = gift_description)What does the tokenized dataset look like?

gift_words_raw %>%

head(11)## # A tibble: 11 x 3

## id donor_country word

## <dbl> <chr> <chr>

## 1 1 Moldova 40

## 2 1 Moldova x

## 3 1 Moldova 29

## 4 1 Moldova gilt

## 5 1 Moldova framed

## 6 1 Moldova oil

## 7 1 Moldova painting

## 8 1 Moldova of

## 9 1 Moldova an

## 10 1 Moldova autumn

## 11 1 Moldova landscapeEach word has its own row, but we can still read the beginning of the first description, a gift from Moldova: “40 x 29 gilt framed oil painting of an autumn landscape”.

What if we stopped now and looked at the most common words used in gifts from Moldova?

gift_words_raw %>%

filter(donor_country == "Moldova") %>%

count(word, sort = TRUE) %>%

head(12)## # A tibble: 12 x 2

## word n

## <chr> <int>

## 1 of 23

## 2 value 19

## 3 est 18

## 4 disposition 16

## 5 rec'd 16

## 6 the 15

## 7 and 11

## 8 to 10

## 9 a 9

## 10 administration 8

## 11 12 7

## 12 4 7Not very insightful. The most common word is “of”, which doesn’t tell me anything about distinctively Moldovan gifts. And there are other words that probably appear in most descriptions. For example, “est” and “value” are probably common because descriptions need to include an est(imated) value!

Eliminating stop words

These common, but not useful, words are called “stop words” and it’s common practice in text analysis to filter them out. For this analysis, we will filter out four types of stop words:

- Standard stop words, like “the”, “or”, “of”, and “a”

- Country stop words, like “Croatian” or “Tanzania”, since these don’t tell us anything useful about the actual gifts

- Description stop words, like “est” and “value”, since they appear in most or all descriptions (and therefore don’t tell us anything useful about the gifts themselves)

- Month stop words, like “January” and “Feb”, because they sometimes appear when the description notes the date of receipt

We’ll also remove any “words” that are just numbers, which usually describe physical dimensions, value, or dates. Numbers used for physical dimensions (e.g., “6 inches x 6 inches”) could be useful, but we’d have to get pretty sophisticated to parse out gift sizes, so we’ll stick with “real” words.

# Country stop words (e.g., Afghani, Croatian, Tanzanian)

source("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/tacookson/data/master/us-government-gifts/src/country-adjective-list.R")

# Description stop words specific to this dataset

gift_stop_words <- c("x", # Used for describing dimensions (e.g, 6" x 6")

"inches",

"est", # Common words about value and disposition

"rec'd",

"recd",

"disposition",

"administration",

"services",

"pending",

"transfer",

"transferred",

"archives",

"protocol",

"gsa",

"national",

"foreign",

"records",

"de", # Stop word in romance languages like French/Spanish

"la",

"los")

# Month stop words

month_stop_words <- str_to_lower(c(month.abb, month.name))

# Put all the stop words together

custom_stop_words <- tibble(stop_word = c(country_stop_words,

gift_stop_words,

month_stop_words)) %>%

unnest_tokens(word, stop_word)Now that we’ve defined our stop words, we use anti_join() to filter them out:

gift_words <- gift_words_raw %>%

# Filter out standard English stop words (or, the, an, etc.)

anti_join(stop_words, by = "word") %>%

# Filter out custom stop words

anti_join(custom_stop_words, by = "word") %>%

# Only keep words that have at least one letter

# Numbers only aren't likely meaningful in our context

filter(str_detect(word, "[a-z]"),

!is.na(donor_country))If we look again at the most common words used to describe gifts from Moldova, now that we have removed stop words, we see much more meaningful terms, like “cognac” and “cricova” (a Moldovan winery). These are way better for answering our question.

gift_words %>%

filter(donor_country == "Moldova") %>%

count(word, sort = TRUE) %>%

head(12)## # A tibble: 12 x 2

## word n

## <chr> <int>

## 1 cognac 7

## 2 bottle 5

## 3 secretary 5

## 4 senate 5

## 5 winery 5

## 6 cricova 4

## 7 cubby 4

## 8 painting 4

## 9 storage 4

## 10 wine 4

## 11 bottles 3

## 12 deposited 3

Calculating TF-IDF

So far we’ve been looking at the most common words – the ones that appear in a country’s descriptions the most times. This measure is called term frequency (the TF in TF-IDF). But it’s a fairly crude measure: it doesn’t take into account that common words for one country could be common words for another country. For example, if we looked at common words – put differently, words with high term frequency – for Moldova and Croatia, we would see that “painting” appears on both lists. So giving a painting might not be a Moldovan thing. Maybe it’s more generally a diplomatic gift thing.

Since we’re interested in gifts that are distinctive to a specific country, we want to know words that show up a lot in one country’s descriptions (high term frequency) but don’t show up a lot in other countries’ descriptions. Inverse document frequency (the IDF in TF-IDF) does this for us: it tells us how common or rare a word is across all descriptions.

Let’s use our Moldova example again. If lots of descriptions (from any country) include the word “painting” and Moldovan descriptions also include many instances of “painting”, then “painting” is not an especially Moldovan word. But if very few descriptions (again, from any country) include the word “cricova” and Moldovan descriptions have lots of instances of “cricova”, then “cricova” probably is a Moldovan thing.

TF-IDF quantifies what we demonstrated in the Moldova example: it is a number that describes how “distinctive” a word is, which turns out to be exactly what we’re interested in. (I won’t go into the formulas for TF-IDF, but if you’re interested, check out Text Mining with R.). With the tidy_text package, we can calculate TF-IDF in one line of code using bind_tf_idf():

gift_words_tfidf <- gift_words %>%

distinct(id, donor_country, word) %>%

count(word, donor_country) %>%

# This calculates TF-IDF

bind_tf_idf(term = word, document = donor_country, n) %>%

# Only include words that appears in at least 3 gift descriptions

filter(n >= 3)Let’s look at the words with highest TF-IDF for Moldova:

gift_words_tfidf %>%

filter(donor_country == "Moldova") %>%

arrange(desc(tf_idf)) %>%

head(6)## # A tibble: 6 x 6

## word donor_country n tf idf tf_idf

## <chr> <chr> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 cognac Moldova 7 0.0470 3.24 0.152

## 2 cricova Moldova 3 0.0201 5.18 0.104

## 3 cubby Moldova 3 0.0201 5.18 0.104

## 4 winery Moldova 3 0.0201 5.18 0.104

## 5 honorary Moldova 3 0.0201 3.80 0.0764

## 6 vintage Moldova 3 0.0201 3.80 0.0764Would you look at that: “cognac” and “cricova” are at the top of the list.

Visualizing TF-IDF

We’ve done the hard work of calculating TF-IDF – now let’s answer our question with it. Specifically, let’s answer three questions with it:

- What are the most distinctive words – those with the highest TF-IDF – overall?

- What words are associated with gifts from G7 countries? (I’m using G7 countries as a proxy for “countries the U.S. has a close diplomatic relationship with”)

- What words are associated with gifts from G20 countries? (Again, I’m using G20 members as a proxy)

Overall top words

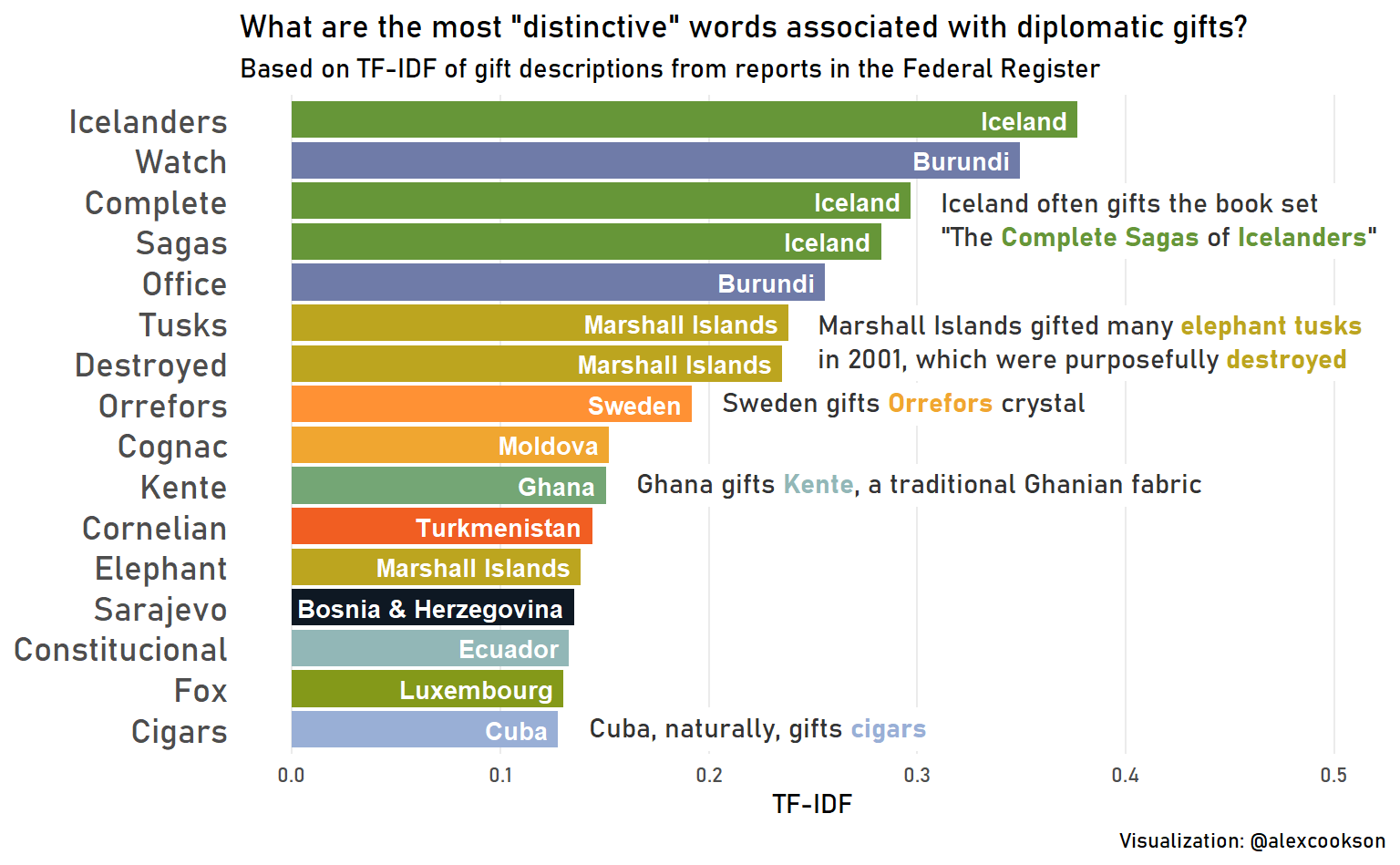

What are the most distinctive words overall, and which countries do they “belong” to? (Sorry for the long, scary-looking code. A lot of it is to add annotations that colour in specific words.)

# Set defaults for annotations so we don't need to copy-paste them

# fill = "white" doesn't work for some reason

update_geom_defaults(GeomRichtext, list(hjust = 0, colour = "grey20", label.colour = NA,

family = "Bahnschrift", size = 4))

gift_words_tfidf %>%

top_n(16, wt = tf_idf) %>%

mutate(word = fct_reorder(str_to_title(word), tf_idf)) %>%

ggplot(aes(tf_idf, word, fill = donor_country)) +

geom_col() +

geom_text(aes(label = donor_country),

size = 3.5,

col = "white",

fontface = "bold",

hjust = 1,

nudge_x = -0.005) +

# Iceland

geom_richtext(x = 0.307, y = 13.5, fill = "white",

label = "Iceland often gifts the book set<br>\"The <span style = 'color:#669638'>**Complete Sagas**</span> of <span style = 'color:#669638'>**Icelanders**</span>\"") +

# Marshall Islands

geom_richtext(x = 0.248, y = 10.5, fill = "white",

label = "Marshall Islands gifted many <span style = 'color:#BCA51F'>**elephant tusks**</span><br>in 2001, which were purposefully <span style = 'color:#BCA51F'>**destroyed**</span>") +

# Sweden

geom_richtext(x = 0.202, y = 9, fill = "white",

label = "Sweden gifts <span style = 'color:#F0A630'>**Orrefors**</span> crystal") +

# Ghana

geom_richtext(x = 0.161, y = 7, hjust = 0, fill = "white",

label = "Ghana gifts <span style = 'color:#92B7B7'>**Kente**</span>, a traditional Ghanian fabric") +

# Cuba

geom_richtext(x = 0.138, y = 1, hjust = 0, fill = "white",

label = "Cuba, naturally, gifts <span style = 'color:#99AFD6'>**cigars**</span>") +

scale_fill_fish("Epibulus_insidiator", discrete = TRUE) +

scale_colour_fish("Epibulus_insidiator", discrete = TRUE) +

expand_limits(x = c(0, 0.5)) +

labs(title = "What are the most \"distinctive\" words associated with diplomatic gifts?",

subtitle = "Based on TF-IDF of gift descriptions from reports in the Federal Register",

caption = "Visualization: @alexcookson",

x = "TF-IDF",

y = NULL) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position = "none",

text = element_text(family = "Bahnschrift"),

panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major.y = element_blank(),

axis.text.y = element_text(size = 14),

strip.background = element_blank(),

strip.text = element_text(colour = "black", face = "bold"))

There are so many cool insights, but I’ll just mention two:

- Iceland seems to like gifting The Complete Sagas of Icelanders, which strikes me as an extremely Icelandic gift to give

- Luxembourg likes to gift fox figurines, which are almost certainly related to Luxembourg’s national epic, Reynard the Fox (Thank you @SophieHeloise for confirming!)

I’ll leave it to you to figure out the significance of the other words. I had fun figuring out how these words were related to their countries. I also learned a ton about specific cultural aspects of some countries.

G7 countries

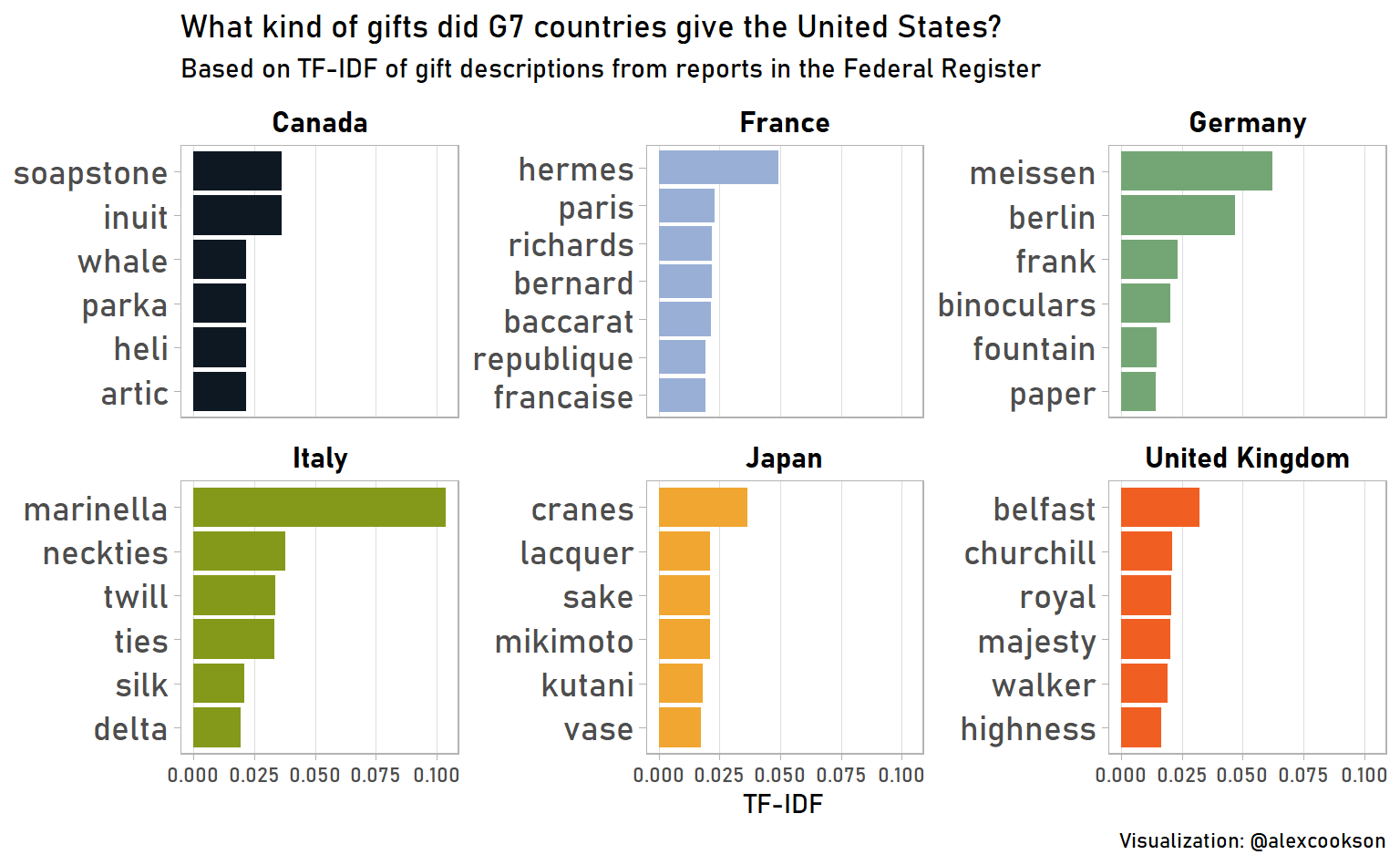

What are the most distinctive words associated with the United States’s fellow G7 countries?

g7_countries <- c("Italy", "Japan", "Germany", "Canada", "United Kingdom", "France")

gift_words_tfidf %>%

filter(donor_country %in% g7_countries) %>%

group_by(donor_country) %>%

top_n(6) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(word = reorder_within(word, by = tf_idf, within = donor_country, sep = ": ")) %>%

ggplot(aes(tf_idf, word, fill = donor_country)) +

geom_col() +

scale_y_reordered(sep = ": ") +

scale_fill_fish(option = "Epibulus_insidiator", discrete = TRUE) +

facet_wrap(~ donor_country, scales = "free_y") +

labs(title = "What kind of gifts did G7 countries give the United States?",

subtitle = "Based on TF-IDF of gift descriptions from reports in the Federal Register",

caption = "Visualization: @alexcookson",

x = "TF-IDF",

y = NULL) +

theme(legend.position = "none",

text = element_text(family = "Bahnschrift"),

panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major.y = element_blank(),

axis.text.y = element_text(size = 14),

strip.background = element_blank(),

strip.text = element_text(colour = "black", face = "bold", size = 12))

Again, I’ll make a few observations and leave it to you to look into the rest on your own:

- France does indeed like to give gifts from Hermès

- Italy likes to give Marinella neckties – in fact, all these gifts are from Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi of Italy, who is apparently a fan of the brand

- Japan often gives gifts featuring cranes

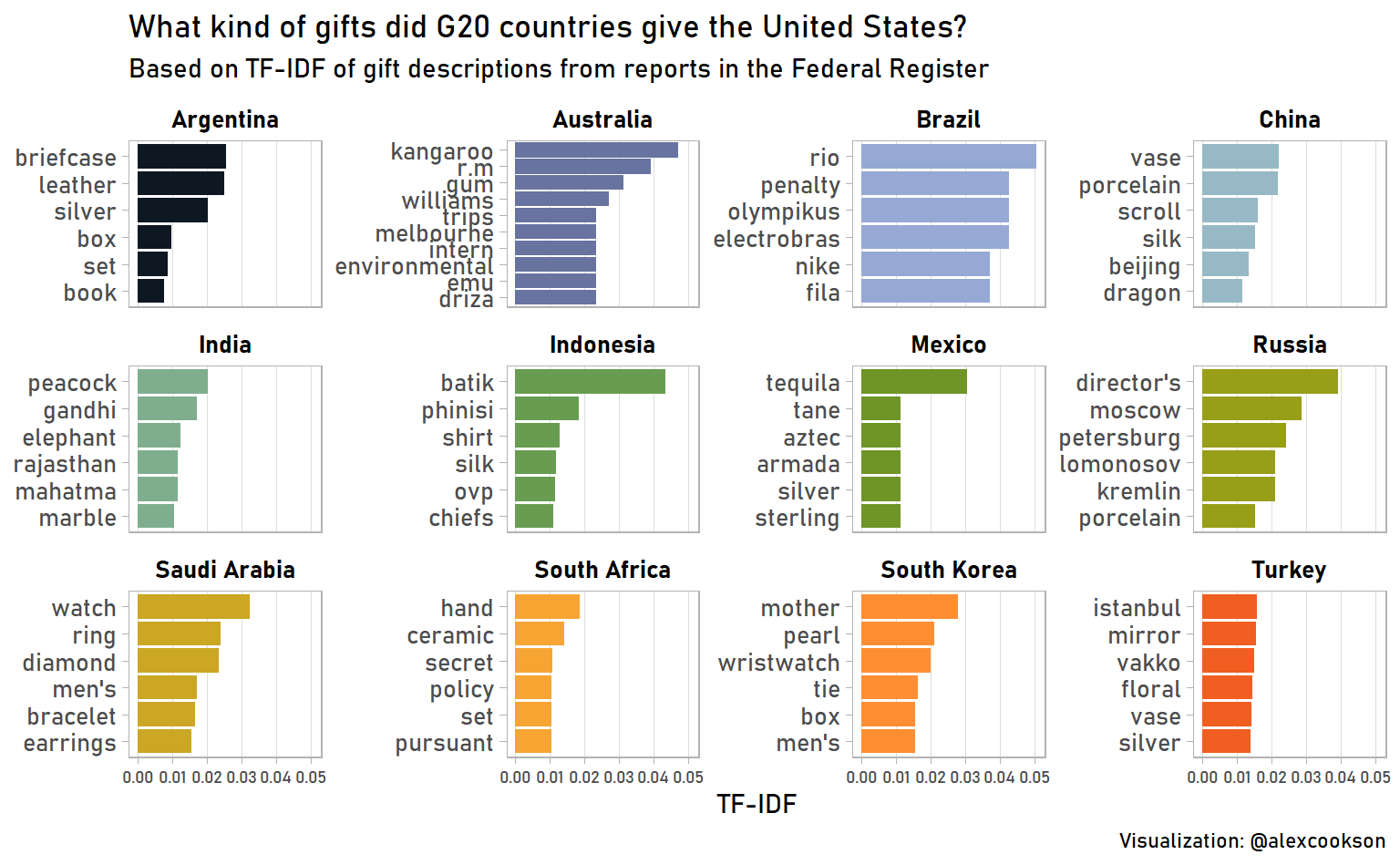

G20 countries

Finally, let’s look at the G20 countries we didn’t already cover when looking at the G7:

g20_countries <- c("Argentina", "Australia", "Brazil", "Canada", "China", "France", "Germany",

"India", "Indonesia", "Italy", "Japan", "Mexico", "Russia", "Saudi Arabia",

"South Africa", "South Korea", "Turkey", "United Kingdom")

gift_words_tfidf %>%

filter(donor_country %in% setdiff(g20_countries, g7_countries)) %>%

group_by(donor_country) %>%

top_n(6) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(word = reorder_within(word, by = tf_idf, within = donor_country, sep = ": ")) %>%

ggplot(aes(tf_idf, word, fill = donor_country)) +

geom_col() +

scale_y_reordered(sep = ": ") +

scale_fill_fish(option = "Epibulus_insidiator", discrete = TRUE) +

facet_wrap(~ donor_country, scales = "free_y") +

labs(title = "What kind of gifts did G20 countries give the United States?",

subtitle = "Based on TF-IDF of gift descriptions from reports in the Federal Register",

caption = "Visualization: @alexcookson",

x = "TF-IDF",

y = NULL) +

theme(legend.position = "none",

text = element_text(family = "Bahnschrift"),

panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major.y = element_blank(),

axis.text.x = element_text(size = 7),

axis.text.y = element_text(size = 10),

strip.background = element_blank(),

strip.text = element_text(colour = "black", face = "bold", size = 10))

A few observations:

- Mexico likes to give bottles of tequila!

- South Korean gifts often feature mother-of-pearl

- Russian gifts are strangely associated with the word “director’s”

The Russian obsversation illustrates a shortcoming of TF-IDF. The high score for “director’s” is a result of Louis Freeh, Director of the FBI, receiving fourteen gifts from a Russian minister, all of which were noted as being “on display in director’s office”. So instead of picking up on attributes of the gifts themselves, we picked up on what the recipient did with them. TF-IDF is quick and useful, but not perfect!

Conclusion

We dove into the dry world of government reporting and came up with some interesting facts, like Japan’s fondness of gifts featuring cranes and Luxembourg’s love of foxes. There are so many other questions we could answer with our data, though, including:

- Do some countries give more expensive gifts than others?

- How has gift-giving changed over time?

- Do specific individuals tend to give certain gifts? (e.g., Silvio Berlusconi giving Marinella neckties)

- Do men and women tend to receive different types of gifts?

- Have different presidents tended to receive different types of gifts?

- Are there regional patterns to gifts? (e.g., Middle Eastern countries gifting rugs)

We could also make our analysis more sophisticated:

- Look at named entities instead of individual words. This would keep things like “leather briefcase” as a single entity, even though it’s two words, instead of separating them into “leather” and “briefcase”. The

spacyrpackage is a great option for this. - Stem or lemmatize words. This would combine words that the same meaning into a single term. For example, Kenya’s descriptions included “elephant” and “elephants”. They were two different terms in our analysis, but they’re not different concepts, so stemming or lemmatization would combine them into a single term.

For now, though, I’m happy with the more straightforward, easy-to-implement TF-IDF approach. If you want to explore this dataset further, feel free to download the raw data and play around with it yourself. And, if you enjoyed this post, please let me know on Twitter.